Feature: Public Artworks by Gallery Artists

The physical experience of art is fundamental. With that in mind, we have put together a list highlighting some of the many public installations by our gallery artists. The works below remain accessible in the U.S. despite the current distancing measures. We hope there is one close to you.

Work by: Carl Andre, Tauba Auerbach, Jennifer Bartlett, Jonathan Borofsky, Sophie Calle, Mark di Suvero, Robert Grosvenor, Hans Haacke, Sol LeWitt, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg & Coosje van Bruggen, Joel Shapiro, Meg Webster

Carl Andre, Stone Field Sculpture, 1977

Corner of Main Street & Gold Street, Hartford, CT

Commissioned by the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving and the National Endowment for the Arts in 1977, Stone Field is Carl Andre’s only outdoor sited sculpture. Consisting of thirty-six boulders placed in eight parallel rows of increasing length, the piece extends across a narrow, sloped lawn to form a triangular configuration. Varying from brownstone, granite, schist, gneiss, basalt and serpentine, the massive boulders allude to New England’s once glaciated landscape; the centuries old tombstones of the adjacent Ancient Burying Ground; and such prehistoric megalithic monuments as Stonehenge and Carnac.

Tauba Auerbach, 2020, 2019

Mosser Towers, San Francisco, CA

Tauba Auerbach's largest painting to date, a monumental mural titled 2020, is on view in San Francisco's Tenderloin neighborhood. Organized by Luggage Store Gallery, the public work was painted in collaboration with New Bohemia Signs, the longest running sign shop in San Francisco, for which Auerbach worked as a sign painter from 2001 to 2004. Combining trompe l’oeil and paper marbling, Auerbach’s work creates a fluid and beguiling spatial logic.

Jennifer Bartlett, St. Stephen's Doors, 1998

St. Stephen's Episcopal Church, Houston, TX

In 1998, St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Houston commissioned Jennifer Bartlett to do a series of colored-glass windows for their columbarium. Visible from the building’s exterior on W. Alabama Street, the eight graphic panels of fused, stained, and painted glass illustrate the artist’s playful categorization of color, shape, and line. Verticals, horizontals, diagonals and dots are ordered and overlaid, forming a concise compendium of abstract patterns. Set within the square glass window panes, the piece recalls Bartlett’s consistent use of the grid as a base structural unit.

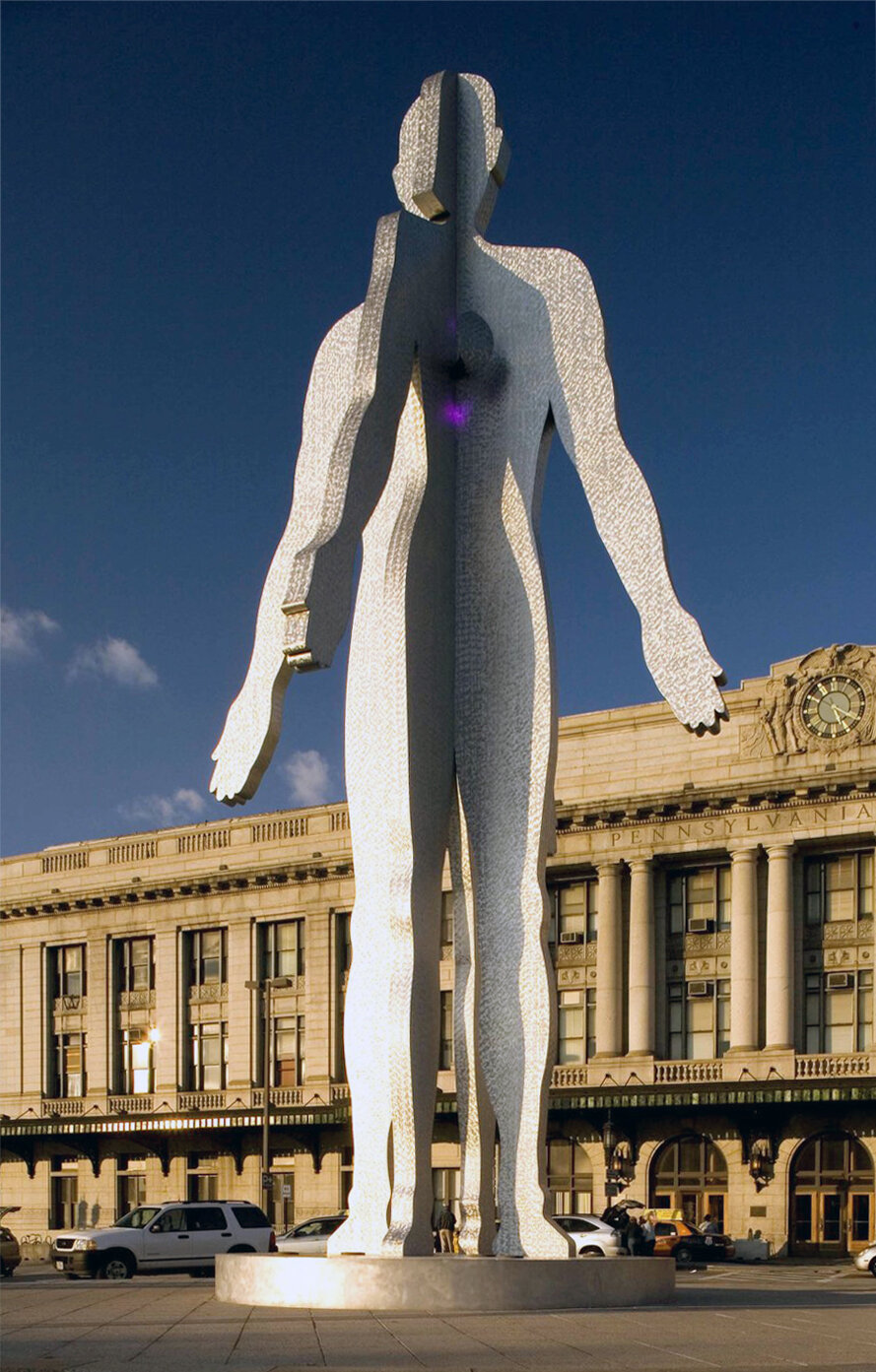

Jonathan Borofsky, Hammering Man, 1991

Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA

Hammering Man is a series of monumental steel sculptures of a silhouette of a man with motorized arm and hammer. Painted black to celebrate workers, models of various sizes in the series have been installed in public spaces and museums throughout the U.S. and Europe, with the first wooden version shown at Paula Cooper Gallery in 1980. Standing at forty-eight feet tall, the Hammering Man in Seattle was installed in 1991. “Let this sculpture be a symbol for all the people of Seattle working with others on the planet to create a happier and more enlightened humanity,” Borofsky stated. “At its heart, society reveres the worker. The Hammering Man is the worker in all of us.”

“I’m not limited to the gallery or museum space anymore [...] It’s more pleasing for me to have my hammering man in Frankfurt with twenty thousand cars driving under it every day for the next hundred years than some painting I could sell to a collector that will someday end up in some museum that will be shown once in a while and otherwise stored in the basement. That’s why I started making larger outdoor pieces.”

Sophie Calle, Here Lie the Secrets of the Visitors of Green-Wood Cemetery, 2017-2042

Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY

Co-presented by Creative Time and Green-Wood Cemetery, Here Lie the Secrets invites the public to unburden and inter their most intimate confessions. Visitors who have transcribed their secrets onto paper may lay them to rest through a slot on a marble obelisk grave designed by the artist. Throughout the work’s twenty-five-year presentation, Calle will return periodically to exhume and cremate the grave’s contents in a ceremonial bonfire service and moment of remembrance. Visit the Green-Wood website for updated hours of operation.

Mark di Suvero, The Calling, 1981-82

Terminus of E. Wisconsin Ave, Milwaukee, WI

Constructed from steel I-beams that erupt outward from a central point of intersection, The Calling stands forty-feet tall at the end of Wisconsin Avenue. Nicknamed the ‘orange sunburst’ by the public, di Suvero proposed the bold color and linear form to complement the site’s backdrop—the large bluff and expansive view of Lake Michigan—as well as to echo the city’s landscape of bisecting streets and vertical buildings. Commissioned by the Milwaukee Art Museum, the sculpture was a gift from the Bradley Family Foundation.

“When one is an artist, one wants to do art that is meaningful to a lot of people. Most art is shown in museums and galleries, which eliminates a whole population. By putting it out on the streets, you open it up to the world […] there’s a great thing that happens when you have outdoor works where people are interacting and searching.”

Robert Grosvenor, Untitled, 1968

Slicing through the landscape in both scale and color, Grosvenor’s large abstract form creates the sense of vertical movement, beginning slowly and shooting upwards leading the viewer’s eye towards the sky. Though programming at Art Omi is currently suspended, visitors are still welcome to explore the grounds.

Hans Haacke, New York Artists’ Memorial Garden, 2019

Jackson Square Park, New York, NY

Presented by the Art Production Fund and White Columns, the New York Artists’ Memorial Garden is a collaborative project honoring the city’s history of artist communities. Each of the thirty-four participating artists were invited to dedicate a bench to an individual or an entity that is significant to them—transforming an existing park into a public artwork and space for reflection. Haacke’s contribution honors the photographer and writer Allan Sekula (1951–2013), whose discursive approach to documentary challenged social relations and labor within global capitalism and trade.

Sol LeWitt, Tower (Lodz), 1993, and Tower (Frankfurt), 1990

Miami Design District, ICA Miami, FL

Each rising over twenty feet high, two monumental Progression Towers by Sol LeWitt—Tower (Frankfurt), 1990, and Tower (Lodz), 1993—mark the entrance to Miami’s Design District. The works were first installed in November 2017 to inaugurate the public sculpture program of the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. Made of pale gray concrete blocks, a humble material that LeWitt first introduced into his work in the 1980s, the modular arrangements illustrate the artist’s career-long interest in elementary progression and egalitarian materials, even while his configurations grew in complexity and variety.

“It was a way of questioning the general perception of art as inaccessible. Just as the development of earth art and installation art stemmed from the idea of taking art out of the galleries, the basis of my involvement with public art is a continuation of wall drawings […]. It is available to be seen by everyone. It avoids the preciousness of gallery or museum installations. Also, since art is a vehicle for the transmission of ideas through form, the reproduction of the form only reinforces the concept. It is the idea that is being reproduced.”

David Novros, Painted windows, Gross House, 1996–1997

422 Old Highway, Route 66, Winslow, AZ

A former bus station on Route 66 was transformed by David Novros during two trips to Winslow, Arizona in the late 1990s. By painting the glass panes in the large windows that wrap around the facade in bold blocks of color, Novros turned the building into a painted place. This site-specific installation was commissioned by the artist’s friend Peter Gross, who used the building as a residence and workshop.

Claes Oldenburg & Coosje van Bruggen, Architect's Handkerchief, 1999

860-880 Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL

With its billowing white form, Architect's Handkerchief offers a strong contextual link to its location in front of the Chicago Landmark "Glass House" apartments. Considered seminal in the International Style and the development of modern High-tech architecture, this twin pair of glass-and-steel towers were designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Architect's Handkerchief pays homage to the renowned architect and his trademark handkerchief—finding its source in a tightly framed photograph by Peter Blake.

“In public sites, our sculptures reflect both the surroundings and their context, but through our imagination and selective perception—which is what makes them also personal. We feel free to use all the approaches that come naturally to our non-monumental works: variations in scale, similes, transformations, a wide range of materials, and, of course, our use of familiar objects.”

Joel Shapiro, Loss and Regeneration, 1993

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

At twenty-five feet tall, the first element of this two-part bronze sculpture is a semi-abstract composition of simple rectangles. Referencing a human stick figure, the structure’s precarious arrangement evokes an ambiguous movement through space. Installed nearby is the second element, resembling an inverted house. The work memorializes the children who perished during the Holocaust and is accompanied by an excerpt of a poem written by a child in the Terezin ghetto. Shapiro likens the overturned house to the subversion of the universal symbol of security, comfort, and continuity. The larger figure is conceived as an emblem of renewal—of the possibility of a future even after all has been lost.

“It was an extremely challenging if not impossible task to make a form that could at least in some manner communicate the profound tragedy and psychotic brutality of that time. The opportunity to try to project all one’s thoughts into a condensed form is irresistible—that is what sculpture is. Life is altered but it continues—that is something that we must recognize.”

Meg Webster, Stonefield, 2010

Pier 64 at West 24th Street, New York, NY

Of the work, Webster stated: “Large stones were chosen from quarries in New York State and northeastern Pennsylvania. Each stone was selected for its special shape and unusual sculptural qualities. Some are colorful, some are concave, some are craggy. One is very tall, and another is shaped somewhat like a boat. Each is special. The stones are arranged to show their unique characteristics and individual ‘being-ness.’”